Update from February 21, 2025: This article was originally published on July 24, 2021.

Forgive me friends.

I promised to write about the storming of the Bastille in 1789, the flashpoint of the original French Revolution, an event commemorated in France each year on July 14th.

But I had to pivot.

As Bastille Day neared, I found myself thinking critically about the meaning, significance, and relevance of national holidays. I questioned their roots in colonialism and their relationship to slavery and other systems of oppression. I wondered why we celebrate with fireworks and military parades. I was not alone. My social media feeds were filled with calls to cancel Canada Day; and, conversely, to recognize Juneteenth as an official holiday in the United States.

Were there similar movements in France? I wondered.

A quick Google search showed me that it is only in English-speaking nations that July 14th is known as Bastille Day. French citizens refer to the day as Fête nationale (National Celebration) or le 14 juillet (the 14th of July). I also learned that the day marks not just the storming of the Bastille in 1789 but also the Fête de la Fédération, a massive celebration of national unity held one year later.

In 1880, when Senator Henri Martin argued that July 14 be adopted as the Fête nationale, he alluded to people’s qualms about commemorating a day of bloodshed and highlighted the dual roots of the celebration.

“This [latter] day cannot be blamed for having shed a drop of blood, for having divided the country. It was the consecration of the unity of France . . . If some of you might have scruples against the first 14 July, they certainly hold none against the second.”

Ambivalence appears to have been baked into the holiday from its inception. And, yet, I could find no evidence of a movement to cancel or, even, re-imagine the National Celebration.

But that doesn’t mean my research wasn’t fruitful. In France, I discovered, people were talking about a different revolution. The third one.

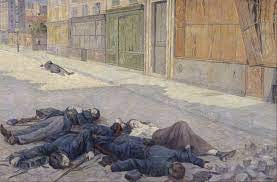

2021 marks the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune, a short-lived social democracy regarded (on the left) for its progressive agenda and maligned (on the right), not only for separating church and state but also for setting fire to the Tuileries Palace and other landmarks. (One of their most symbolic acts—depicted in the engraving at the top of this post—was to burn a wooden guillotine, a symbol of State oppression.)

From March 18 to May 28, 1871, the Commune established feminist, socialist, and anarchist policies that addressed issues as diverse as policing and child labour, creating what Frederich Engels called the first example of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The Commune ended in la semaine sanglante (the bloody week). At least 6,000 Communards (as they were known) died. Likely more. (They also did their fair share of killing in retaliation.)

As the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune approached, livestream events were planned. Articles published. Podcasts produced. Yet, not everyone was celebrating. As Adam Gopnik noted in “The fires of Paris” (The New Yorker, 2014): people still fight about the Paris Commune. Why?

In this issue of Sift. Shift. Lift. I attempt to answer that question.

Ready? C’est parti.

Sift.

Sift through contemporary accounts, news articles, and academic research to better understand the history and legacy of the Paris Commune.

Just looking for a brief overview?

“Viva la Commune? The working class insurrection that shook the world” by Julian Coman. (The Guardian, March 7, 2021)

“The embers of a long-smoldering revolution are stoked in France” by Constant Méheut. (The New York Times, April 28, 2021)

On the go?

Tag along as John Merriman, Charles Seymour Professor of History at Yale University, and author of Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune (Basic Books, 2014), takes IDEAS producer Philip Coulter on a guided tour in “Fire and blood: The Paris Commune of 1871”. (CBC Radio, May 28, 2015)

Listen to “Why the Paris Commune burned the guillotine—and we should too” on The fire these times. (March 25, 2020)

Want to dig deep?

Put your library card to use. Check out “Under the Flag of the Universal Republic: Essential Paris Commune Reading List” from Verso Books, and “150 years of the Paris Commune: A reading list” from Haymarket Books.

Spotlight on La Commune 2021

Head back to school with La Commune 2021, a free, 10-week, online crash course on the Paris Commune, developed by writer and scholar Roxanne Panchasi in partnership with UNIT/PITT Society for Art and Critical Awareness.

The course, which coincided with the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune is officially over, but you can still access the wealth of resources Panchasi curated online, including contemporary accounts, articles, books, manifestos, photographs, interviews and a timeline.

One of my favourite features of La Commune 2021 is Radio 1871, an interview series Panchasi originally created for a seminar she offered at Simon Fraser University. Art and artists (of all kinds) feature prominently in the far-ranging discussions she has with her guests, from the value of studying works of art as historical documents to the Manifesto of the Paris Commune’s Federation of Artists.

Curious? Check out:

Episode 2: Manifestos! with Dr. Sarah Osment, a lecturer at New College of Florida in Sarasota

Episode 5: Art and artists with Dr. Clint Burnham, a professor in the Department of English at Simon Fraser University

Episode 6: Internationalism with Dr. Michelle Coghlan, Senior Lecturer in American Literature at the University of Manchester

Shift.

Let art, music, and literature shift or deepen your understanding of the Paris Commune.

Visual Art

Read “The iconography of the Paris Commune, 150 years later” by Billy Anania. (Hyperallergic, May 27, 2021)

Learn about “The Commune’s Marianne: An art history of la pétroleuse” in this essay by Lynn Clement, adjunct professor of Art History at Northern Virginia Community College and the College of Southern Maryland. (June 12, 2017)

Literature

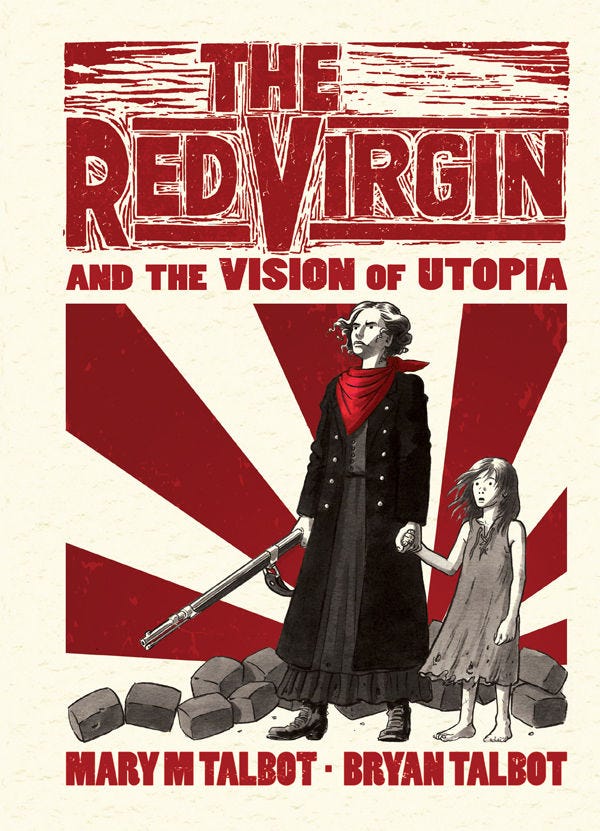

I’d be remiss if I didn’t recommend The red virgin and the vision of utopia (Mary M. Talbot, Dark Horse Comics, 2016), a graphic novel about French anarchist Louise Michel. It is the book that first introduced me to the Communards.

As much as I love historical fiction, I am also keenly interested in stories and poetry written by people who lived at the time of the Paris Commune. And, so, I am adding these books to my ever-growing to-be-read list:

The child by Jules Vallès (Penguin Random House, 2005)

La débâcle by Émile Zola (Oxford World’s Classics, 2000)

The pilgrims of hope by William Morris (Cullen Press, 2016)

(The award for most intriguing title set against the Paris Commune goes to The werewolf of Paris, a horror novel by American writer Guy Endore in 1933.)

Theatre and film

Watch an excerpt from the acclaimed film La Commune (Paris, 1871) directed by Peter Watkins. (2000)

Listen to artist Zoe Beloff discuss the Paris Commune, Occupy Wall Street, and her 2008 street-based production of Bertol Brecht’s play, Days of the Commune.

Music

The history of the Paris Commune is inextricably tied to music. It was there, after all, that the lyrics to the L’Internationale anthem were penned by Eugène Pottier.

Listen to the L’Internationale and other “Songs of the Paris Commune.”

Read about “The fancy concerts of the Paris Commune.” (Livia Gershon, JSTOR Daily, May 17, 2021)

Lift.

Take action. The spirit of the Paris Commune lives on in progressive, grassroots movements.

Idle No More calls on all people to join in a peaceful revolution to honour Indigenous sovereignty and to protect the land & water & sky.

Occupy Wall Street is a “people-powered movement that began on September 17, 2011 in Liberty Square in Manhattan’s Financial District, and has spread to over 100 cities in the United States and actions in over 1,500 cities globally.”

#BlackLivesMatter was founded in the United States in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer. It has grown into the Black Lives Matter Foundation, a global organization in the U.S., United Kingdom and, my home country, Canada.

“We live in a time of great fears, too many are still looking for their own way out of trouble, but we say: fight together, this is the only way we can achieve freedom and justice.” — Louise Michel

Thanks for reading Sift. Shift. Lift. I know your time is limited, so I am honoured you chose to spend some of it here with me. Know anyone else who’d like to join us?

Until next time,

Shelley

Wow! Exhaustive, educational, and so well done. I'm very glad I subscribed!